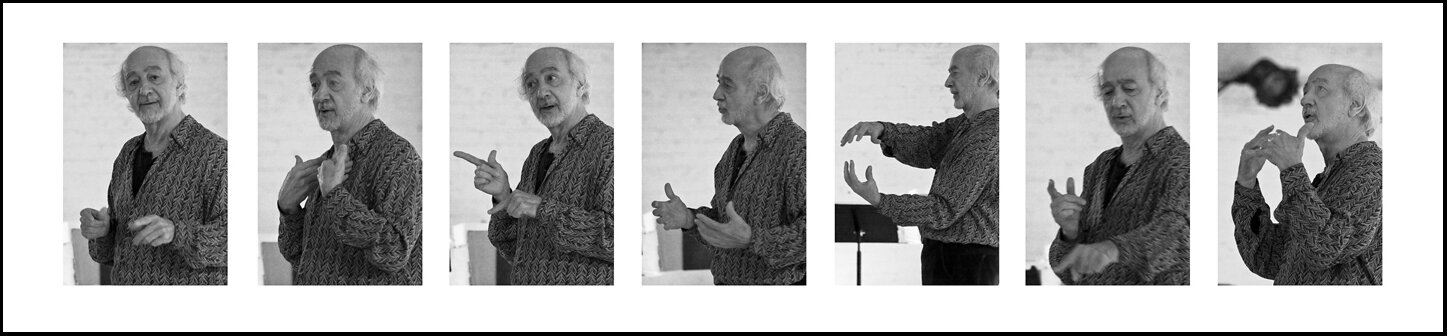

Photo by Marc Perlish

Journey to the Seed: dream, imagination and memory in Julio Estrada’s music by Pablo Santiago Chin

Around forty years ago Julio Estrada dreamt or imagined (now it is a vague memory) that he was under water staring at a luminous sphere. He was moving, and with his motion the lights would morph, coming through the frame of four windows surrounding the sphere. Later Estrada imagined this vision as music, always resulting in a similar, but not identical music. Dream, imagination and memory conjured up the creative impulses that led Estrada to design a compositional method based on drawings of curving lines representing sonic energies. Moving from left to right and carrying different colors, the drawings expressed energy trajectories that could match various components of a sonic “fabric” described by Estrada as macro-timbre. Such was the foundation of Estrada’s Yuunohui cycle, one of his most daring artistic projects to this day.

Yuunohui’yei for cello was created in 1983. Dedicated to Rohan de Saram, yei inaugurated a series of solo pieces emanating from the conversion of the drawings to music notation. The creation of the Yuunohui series encompasses thirty years, still to be completed by Yuunohi’sa for voice. There are versions for all strings (yei, nahui, se and ome), keyboards (tlapoa), a noise maker (wah), and all wind instruments (ehecatl). These pieces can be performed as solos or simultaneously, in combinations of duos, trios, quartets and so on. There is a mobile characteristic in the conversion of the drawings, meaning that any curve could represent more than one aspect of complex sounds. Thus in yei the blue strokes become dynamics while in nahui (for double bass) they are assigned to pitches. Other aspects of these complex sounds are specific to instrumental actions, like bow changes, which in yei correspond to the red drawings while in nahui correspond to the yellow ones. These sound components, contingent on each instrument's capacities, are woven as the various voices of a polyphonic texture. Such texture forms the macro-timbre, the essence of each of the eight sections in which the Yuunohui is articulated.

Graphic for Section VI of Yuunohui

A dream may have arguably catalyzed the genesis of Yuunohui; but more importantly, Estrada turning his attention to the depths of the mind revealed a new path in his expressive endeavors. More remarkable than mimicking in art the representational facade of dreams is to find in them paradigms of operation. Estrada’s new method founded upon processes of conversions, and rooted in the pictorial recording of inner sonic fantasies highly resembles dreams as analyzed by Freud. For Freud, a dream is a mode of expression. So is art. That which is expressed in dreams (the dream content) may include experiences and feelings like fear or desire (the dream thoughts) which are distorted when dueling with censoring agents such as cultural impositions or moral beliefs. According to Freud “the dream-content seems like a transcript of the dream-thoughts into another mode of expression.” [1]

If transcription can also be a form of conversion, the score of Yuunohui is a conversion of drawings, themselves a pictorial conversion of the creator’s pure, inner sounds. Imagery and conversion lie at the heart of both the Yuunohui and Freud’s Dream Theory. Furthermore, let’s recall the role of dueling with censoring agents in rendering the peculiar form of dreams, according to Freud. If a dream may have been the catalyst that led to Yuunohui, a rebellious drive fueled Estrada’s development of the graphic-recording method utilized in these pieces. After years of conventional musical practices influenced by instructors like Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Mesiaen, Estrada realized that composing with methods based on discrete units of sound (e.g. scales, pitch series, or rhythmic figures) was an obstruction to expressing his authentic sonic fantasies. After this realization Estrada “resigned from being a composer, and [he] started to be more of...an artist who integrates his vital experiences...in what he’s going to produce.” [2]

With the graphic-recording method and working with the continuum in sound, Estrada “finally cut[s his] umbilical chord with the conservatory.” [3] In the continuum he finds affinity with the type of sounds he imagines. Only a few years before embarking on this radical exploration, Estrada was still composing with tempered, discrete pitches and rhythmic figures based on conventional divisions of unit beats. Nonetheless, in his Canto Alterno from 1978, hints of his concerns with the underpinnings of the imagination resulted in a labyrinthine, mobile structure. A complex web-like spiral at the center of the score indicates a myriad of routes for the performer to break the linear succession of the piece’s twelve sections. Not only the sections can be performed in any order, but fragments within sections can also lead into one another. While the quasi-Bachian compound melodies based on intervals of thirds and seconds tie Canto Alterno with Western tradition, the work’s puzzling form suggests a novel narrative similar to stream of consciousness. Estrada thus found a way of approximating the spontaneity and looseness with which musical ideas emerge in the imagination.

Sketch mapping the formal choices for a cellist in Canto Alterno

To restrain expression to constructions based on prevalent musical vocabularies became an obstacle to the sonic fantasies Estrada anticipated in Canto Alterno. A key source of inspiration to leave this obstacle behind is nature. In an interview with Carlos Sandoval, Estrada said that “to be able to return, by way of the graphic, to acoustic structures closer to nature, we can access less abstract musical forms, that by their aspect can be identified as figurative.” [4] Hence Estrada’s fascination with the literature of Juan Rulfo that inspired his opera Murmullos del Páramo. Drops of water falling on rocks, water over wet soil, the sound of ghostly voices carried on the wind, and “the unnamable noise”: these are sounds of memory and imagination. Estrada’s reflection on natural sounds versus abstract forms resonates with Herbert Marcuse’s analysis of Freudian theory when he affirms that “the effective subjugation of the instincts to repressive controls is imposed not by nature but by man.” [5] The influence of Carlos Chávez, Messiaen and Boulanger was still significant in 1978 despite Estrada’s abundant creativity. Marcuse continues:

“The primal father, as the archetype of domination, initiates the chain reaction of enslavement, rebellion, and reinforced domination which marks the history of civilization. […] The struggle against freedom reproduces itself in the psyche of man, as the self-repression of the repressed individual, and his self-repression sustains his masters and their institutions. It is this mental dynamic which Freud unfolds as the dynamic of civilization.” [6]

Beyond the primal father is the primal self. Before dream there is memory. Estrada also considers childhood as a source of material in the formulation of his musical thinking. For him, it was essential to develop the use of the graphic recording and conversion method in order to liberate those early impulses. Besides Canto Alterno, in 1978 Estrada also learned about the UPIC system developed by Xenakis. Coming across the UPIC was a defining moment in Estrada’s path to exploring the free possibilities of the continuum. The UPIC allows drawings made on a large board to be translated into sound by a computer, using the horizontal and vertical axes as the basis to define time and pitch. Xenakis believed that children produced the most interesting sounds through drawing on the UPIC. [7] In regards to that computer program in which Xenakis composed that same year his well known electronic piece Légend d’Ér, Estrada says:

“The recovering of the intuitive [from the experience using the UPIC] contributed to revolutionize my compositional thinking. That experience allowed me to recover, for example, those movements from the imaginary that I had as a child, at 10-years old, that had a profile similar to that of my recent fantasies (what is particular is how they used to occurred: first, within a rigid musical style and, then, displayed throughout a free space).” [8]

Xenakis teaching the UPIC system to kids

In his music, Estrada seems to yearn for a primal element that is also inherent to childhood. This element is embodied by the sounds of ‘newborn babies crying, of tiresome, drowsiness, hunger, colic, and fear.’ [9] To the private world of the composer’s imagination, now is also added an aspect of common codes: ‘[These sounds] are universal; belong, above cultures, to what in my understanding would be germs of the expressivity of metaphysical character that chant inherits […] I think that the evolution of the knowledge of the psychic universe can contribute to reach in each of us the different registers of that chant, to try to incorporate in music those distinctive voices. What is essential is to do it in an autonomous and individual manner.’ [10]

Dream and memory are ingredients of the modernist collective imagination in Mexican art. From 19th century Indianismo to 20th century Indigenismo, Mexican artists have been concerned with a pre-colonial language of which only incomplete traces remain. An important part of Estrada’s academic writing has focused on the music of composers from both of these traditions. While he acknowledges the modernist incorporation of native instruments to the orchestral palette and the recovery of the repetitive in indigenous musics, Estrada is also critical towards the hypothetical reality of these fantasies which supposed all primitive peoples must have used the pentatonic scale. [11] In 1978 Estrada composed Canto Alterno and discovered the UPIC. That same year, while meeting Xenakis in Teotihuacán, he told Estrada:

“[...] how ingenuous and inconsequent it is to believe that what today remains of those [indigenous] peoples has to do with what pre hispanic cultures were like. Everything sounds like Spain: instruments and hispanic-arabic melodic tropes mixed with remnants of instruments which are slowly disappearing. [The legacy of monumental and sophisticated architecture, urbanist design and pictorial ornamentation] is testimony of a culture that must have cultivated music in a much higher level than it is presumed.” [12]

For Estrada ‘the graphic recording method can give access to a space that may have existed in antiquity, in moments of proximity with the first fantasies of man, where scalistic and stylistic cultural limits did not yet exist.’ In that sense, his search is not just personal, but universal, and detached from nationalistic urges as suggested by Mexican tradition. Largely stolen, Mexico’s infancy and the infancy of the Americas still expresses in the dreams of those who long for purity of expression. Purity of expression and perception can also be found in childhood. Drawing fluctuating sounds in the UPIC revived in Estrada “the importance of his relationship with the wind since childhood, so close to the human voice, and which voice [he] encounters in Rulfo’s texts.” Ehecatl is the deity of wind for the Aztecs, and the suffix of his latest Yuunohui from 2012. Yuunohui is the Zapotec word for mud, wet soil, itself a metaphor for the continuum. Dreams of pre hispanic Mexico, Rulfo and the imagination, memories of childhood and dueling with the primal father, all converged in the latest of a series encompassing more than thirty years, both moving forward and searching back. As in Cuban writer and musicologist Alejo Carpentier’s story Viaje a la semilla, Estrada’s artistic search may be a journey to the seed.

First page of Yuunohui’ehecatl

Footnotes

[1] Sigmund Freud, “The interpretation of dreams,” in Art in theory, 1900-2000: an anthology of changing ideas, ed. By Charles Harrison et al. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2003), 400.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Semichon, Aurélie, and TV UNAM. Murmullos de Julio Estrada. Directed by Aurélie Semichon. 2012. Mexico City: UNAM, 2012. Redtv IES.

[4] Carlos Sandoval, “Entrevista a Julio Estrada.” Heterofonía 108 (1993): 1

[5] Marcuse, Harbert. “Eros and Civilization.”

[6] Ibid.

[7] Xenakis, “Determinacy”, 151. The apparent simplicity in the operation of the UPIC suggests an interesting possibility for non-musicians to compose. Xenakis notes that in the UPIC, children between the age of ten and twelve, and adults with no knowledge of playing a musical instrument are the ones who create the drawings that produce the most interesting. These are individuals with no musical preconceptions, which points to an enhanced level of reliance on intuition during the creative process.

[8] Sandoval, “Entrevista”, 62.

[9] Ibid., 69.

[10] Ibid., 69

[11] Estrada, Julio. “Raíces y Tradición en la Música Nueva de México y de América Latina.” Latin American Music Review, Vol. 3 No. 2 (Autum - Winter 1982): 188-206

[12] Ibid.